Abstract

Introduction: In 2005 the life expectancy for adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) in Los Angeles (LA) county was 35-38 years (Powars 2005), lower than the national average. Lack of access to care was a significant factor in these early deaths. By comparison, the lifespan of patients in the UK National Health Service is much longer (Gardner 2016). In 2009 the only comprehensive adult sickle cell program in LA outside the Kaiser system closed. The California Department of Public Health found that 51% of the adults in CA with SCD live in LA county (Paulukonis 2014). Thus the majority of the 1500 adults living in the largest county in the US have had no access to comprehensive care for over 7 years. The problem is especially acute in southern LA county where many of the adults reside. The dearth of programs for adults drives them to seek recurrent care in emergency departments. Recognizing this as a county-wide public health issue, the LA Department of Health partnered with the Pacific Sickle Cell Regional Collaborative (PSCRC) in 2015 to establish an advanced practice medical home at the Martin Luther King Jr. Outpatient Center to fill this important gap in services.

Methods: The PSCRC was formed when we received a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in 2014. One of the aims of this grant was to improve access to care for adults. The Sickle Cell Clinic at MLK OPC is the result of a collaboration with the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California, PSCRC and the LA County Department of Health Services (LACDHS). Representatives from PSCRC initially approached the CMO of LACDHS to identify the need. Based on demographic data organized by zip code, a concentration of a projected 1000 adults was noted to live in South Los Angeles in the catchment area for MLK OPC. In discussion with the chief medical officer at MLK OPC, the team decided to pursue a whole-person approach to SCD care that would include integrated primary care, specialty services, mental health treatment, and complementary medicine in the same site.

Results: After intense and focused planning, including a PR campaign, the clinic opened August 2016. The staff includes a hematologist with expertise in SCD, a primary care provider, a nurse educator and two community health workers trained by the Foundation. In the first 10 months we have cared for 23 patients. All but two of these patients are from the south LA county area. The age range of the patients is 20-62 years of age. The majority of the patients are genotype SS. All patients were on Medicaid or Medicare insurance.

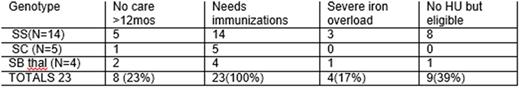

This first cohort of patients is notable for health complications due to lack of coordinated, preventive services. This was measured by a number of indicators: outpatient visits in the 12 months prior to coming to MLK, immunizations, iron overload, and use of Hydroxyurea (HU) (Table 1). One quarter of the patients had no care other than ED or inpatient care for the 12 months preceeding their first visit to our clinic. 100% of the patients had were missing one or more adult immunizations (hepatitis B, tetanus, pneumococcal disease, meningitis, seasonal flu, HPV).Three patients are severely iron overloaded due to multiple transfusions as inpatients with no hematology follow up to address chelation issues. One of those patients required a liver transplant. 39% of the patients (9 patients) seen were eligible for HU but were not on the drug. 17% (4 patients) were on the drug but were noncompliant or poorly managed with episodes of neutropenia. Of those 13 total patients, 11 are now on HU with good compliance and excellent monitoring of drug.

Conclusion: The creation of an advance practice medical home for adults with SCD in Los Angeles demonstrates a successful regional approach that engages medicine, public health, and community based organization leaders to build SCD clinical services in less than a year. This safety net clinic now provides team based primary and specialty care to adults whose only option previously was an emergency room. Our early statistics demonstrate that many patients were not getting appropriate care for their disease due to lack of primary and hematology access. As our patient numbers grow, we expect to see continued improvement for patients which will be measured through a new CDC surveillance project which will track utilization and health outcomes. This model holds promise for replication in other locales to effectively address national inequities in sickle cell care.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.